De laatste tijd probeer ik vaker naar de bron terug te gaan van citaten die vaak voorkomen in de boeken die ik lees. Zo verdiepte ik me laatst in Maslows behoeftenhiërarchie (met twee verrassingen tot gevolg) en dit weekend las ik The Writing Life van Annie Dillard omdat ik dit zinnetje vaak tegenkwam:

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

Als schrijvers zoals Ryan Holiday of Tim Ferriss deze zin citeren, bedoelen ze ermee te zeggen dat je voldoening kunt vinden in het dagelijks leven, in tegenstelling tot in uitzonderlijke evenementen zoals vakanties of feesten. Geluk is wat je op een doodnormale woensdagmiddag doet.

De context van het zinnetje blijkt een ode aan een consistent schrijfschema:

How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order—willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living. Each day is the same, so you remember the series afterward as a blurred and powerful pattern.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

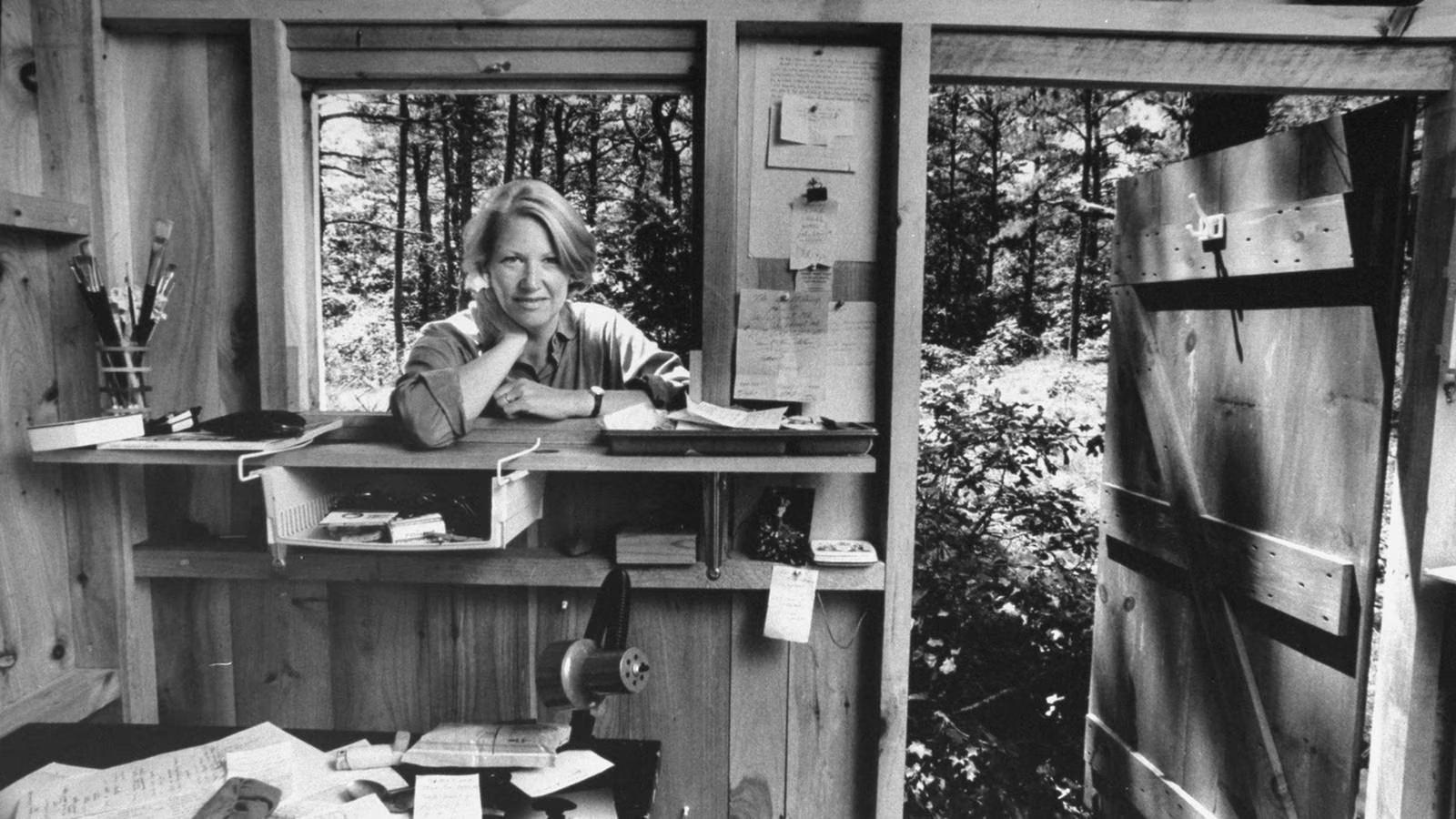

Annie Dillard dankt haar faam aan het boek Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974). Daarmee won ze de Pulitzerprijs en naar ik begrijp bevat het prachtige observaties van de natuur en leest als een aanmoediging om met nieuwsgierigheid naar onze directe omgeving te kijken. In The Writing Life komen dat soort observaties ook terug:

The window looked out on a bit of sandflat overgrown with thick, varicolored mosses; there were a few small firs where the sandflat met the cobble beach; and there was the water: Puget Sound, and all the sky over it and all the other wild islands in the distance under the sky. It was very grand. But you get used to it.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Wat een heerlijke laatste droge zin hè?

Dillard is wars van schrijversromantiek

Met hun imponerende bureau’s, chique vulpennen en een satijnen kamerjas. Zij is meer van het spartaanse soort:

Appealing workplaces are to be avoided. One wants a room with no view, so imagination can meet memory in the dark. When I furnished this study seven years ago, I pushed the long desk against a blank wall, so I could not see from either window. Once, fifteen years ago, I wrote in a cinder-block cell over a parking lot. It overlooked a tar-and-gravel roof. This pine shed under trees is not quite so good as the cinder-block study was, but it will do.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Met een verlangen naar roem of het schrijversleven moet je ook niet komen aanzetten

Je houdt van het vak, van het worstelen van zinnen:

A well-known writer got collared by a university student who asked, “Do you think I could be a writer?” “Well,” the writer said, “I don’t know…. Do you like sentences?” The writer could see the student’s amazement. Sentences? Do I like sentences? I am twenty years old and do I like sentences? If he had liked sentences, of course, he could begin, like a joyful painter I knew. I asked him how he came to be a painter. He said, “I liked the smell of the paint.”

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Zo, nu weten we van wie we schrijfadvies aannemen. Dit vond ik waarachtige schrijflessen van Dillard. Ik heb belangrijke zinnen vetgedrukt:

Hoe je een onderwerp kiest:

People love pretty much the same things best. A writer looking for subjects inquires not after what he loves best, but after what he alone loves at all. Strange seizures beset us. Frank Conroy loves his yo-yo tricks, Emily Dickinson her slant of light; Richard Selzer loves the glistening peritoneum, Faulkner the muddy bottom of a little girl’s drawers visible when she’s up a pear tree.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

En ja, dat kan heel, heel particulier zijn (dat is de bedoeling)

Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain. It is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment. “The most demanding part of living a lifetime as an artist is the strict discipline of forcing oneself to work steadfastly along the nerve of one’s own most intimate sensitivity.” Anne Truitt, the sculptor, said this.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Hoe belangrijk het beheersen van je stemming is:

Remarkably material also is the writer’s attempt to control his own energies so he can work. He must be sufficiently excited to rouse himself to the task at hand, and not so excited he cannot sit down to it. He must have faith sufficient to impel and renew the work, yet not so much faith he fancies he is writing well when he is not.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Waarom het belangrijk is dat je elke dag komt opdagen:

I do not so much write a book as sit up with it, as with a dying friend. During visiting hours, I enter its room with dread and sympathy for its many disorders. I hold its hand and hope it will get better. This tender relationship can change in a twinkling. If you skip a visit or two, a work in progress will turn on you. A work in progress quickly becomes feral. It reverts to a wild state overnight. It is barely domesticated, a mustang on which you one day fastened a halter, but which now you cannot catch. It is a lion you cage in your study. As the work grows, it gets harder to control; it is a lion growing in strength. You must visit it every day and reassert your mastery over it.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Ben je bang voor andermans oordeel tijdens het schrijven? Dillard heeft de oplossing:

Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Wees ambitieus met je teksten, om de volgende logische reden:

It is no less difficult to write sentences in a recipe than sentences in Moby-Dick. So you might as well write Moby-Dick.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Na het aanvankelijke enthousiasme over een tekst, begint het echte werk:

Writing every book, the writer must solve two problems: Can it be done? and, Can I do it? Every book has an intrinsic impossibility, which its writer discovers as soon as his first excitement dwindles. The problem is structural; it is insoluble; it is why no one can ever write this book. Complex stories, essays, and poems have this problem, too—the prohibitive structural defect the writer wishes he had never noticed. He writes it in spite of that. He finds ways to minimize the difficulty; he strengthens other virtues; he cantilevers the whole narrative out into thin air, and it holds. And if it can be done, then he can do it, and only he. For there is nothing in the material for this book that suggests to anyone but him alone its possibilities for meaning and feeling.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)

Durf alles te delen

Ik eindig graag met een observatie van Dillard die precies omschrijft waarom ik dit soort leesverslagen deel:

The impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

Annie Dillard – The Writing Life (1989)